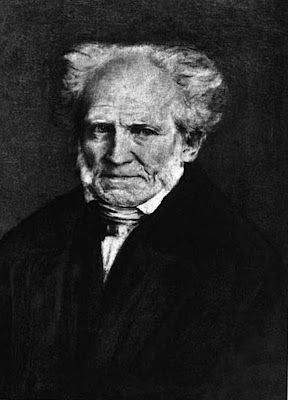

| Arthur Schopenhauer as a young man by Ludwig Sigismund Ruhl (1794–1887) This image is in the public domain in the United States, where Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. See Circular 1 "COPYRIGHT BASICS" PDF from the U.S. Copyright Office. Works published before 1924 are now in the public domain. |

This applies to the United States, where Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. See Circular 1 "COPYRIGHT BASICS" PDF from the U.S. Copyright Office. Works published before 1924 are now in the public domain and also in countries that figure copyright from the date of death of the artist (post mortem auctoris in this case Ludwig Sigismund Ruhl 1794–1887) and that most commonly run for a period of 50 to 70 years from December 31st of that year.

See Circular 1 "COPYRIGHT BASICS" PDF from the U.S. Copyright Office. Works published before 1924 are now in the public domain.The original two-dimensional work shown in this image is free content because: This image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired.

This applies to the United States, where Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. See Circular 1 "COPYRIGHT BASICS" PDF from the U.S. Copyright Office. Works published before 1924 are now in the public domain and also in countries that figure copyright from the date of death of the artist (post mortem auctoris in this case 13 December 1836 – 6 May 1904) and that most commonly run for a period of 50 to 70 years from December 31st of that year.

Arthur Schopenhauer was born in 1788, died in 1860.* His father, Heinrich Schopenhauer, was a wealthy merchant of Dantzic, of strong political opinions, cosmopolitan interests, and independence of thought. His mother was Johanna Schopenhauer, a graceful and refined lady of literary instincts and ambitions, who, after her husband's death, attained to some degree of success as an authoress. From the standpoint of heredity Schopenhauer was unfortunate on the father's side, as there were in the fanner strong tendencies to mental alienation that appeared in the son in the form of eccentricities, groundless fears, and suspiciousness.

On his mother's side he also suffered in environment, for according to Schopenhauer's testimony, her method of dealing with him was unsympathetic. It must be granted that he was not an easy individual to deal with. His mother's butterfly vanity and her selfishness, her method of snubbing, mortifying, and disparaging her son were unfortunate and injurious in their influence. She did not seem to have the true mother instinct of love which Schopenhauer sadly needed. While Kant could recall the tender solicitude and pious influence of a godly and deeply affectionate mother molding his whole life, Schopenhauer could accuse his mother of frivolity and heartlessness. Not that she was positively cruel, but simply lacking in regard for her son.

The Essays of Schopenhauer comprised in this volume are well designated by the title which specially pertains to the first Essay. It will be noticed that the earlier essays are predominantly theoretical or metaphysical, the later practical or ethical. Hence we have in these Essays Schopenhauer's views upon a number of important problems in Metaphysics and Ethics, valuable, as an introduction to his more abstract expositions, to the specialist in philosophy, and yet presented in such a manner as to appeal to the general reader and student of literature.

Among philosophical writers Schopenhauer enjoys the advantage of standing alone. He cannot be classified. He thus escapes being lost in the crowd. It is indeed true that a great deal of what he writes is taken from his predecessors. It is, however, borrowed, not stolen. It is in each case acknowledged and accredited to the original authors, and while it is adopted by Schopenhauer it is so assimilated and transmuted as to become his own, bearing his image and superscription.

He also possesses the advantage of a distinctive and polished literary style. He has a highly developed artistic sense and in accordance with this selects and arranges his material in a form of expression pleasing to his readers. Although a recluse and given to the habit of talking to himself, when he writes he talks to his reader frankly and entertainingly. While he does not even pretend to practice what he preaches in regard to ethical matters, it will be found that his views on the writing of literature are practiced by himself. For instance, note the advice to writers upon the choice of a title. How well has he succeeded in this. Each of his writings has a title appropriate, striking, suggestive, illuminating.

No comments:

Post a Comment