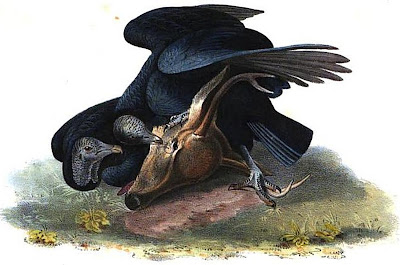

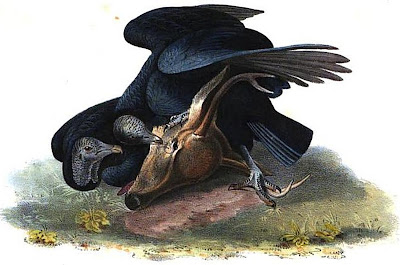

| Black Vulture, or Carrion Crow. I have represented a pair of Carrion Crows or Black Vultures in full plumage, engaged with the head of our Common Deer, the Cervus virginianus. Cathahtes Athatus, Wilson. PLATE III.—Male And Female. |

Title: The birds of America: from drawings made in the United States and their territories. Volume 1 of The Birds of America, John James Audubon. The Birds of America: From Drawings Made in the United States and Their Territories, John James Audubon. Author: John James Audubon (April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851). Publisher: J.J. Audubon, 1840. Original from: Harvard University. Digitized: Jun 12, 2007.

This Image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to the United States, where Works published prior to 1923 are copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. See

Circular 1 "COPYRIGHT BASICS" PDF from the U.S. Copyright Office. Works published before 1923 (in this case

1840) are now in the public domain.

This file is also in the public domain in countries that figure copyright from the date of death of the artist (post mortem auctoris in this case John James Audubon (April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851), and that most commonly runs for a period of 50 to 70 years from December 31 of that year.

This bird is a constant resident in all our southern States, extends far up the Mississippi, and continues the whole year in Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and even in the State of Ohio as far as Cincinnati. Along the Atlantic coast it is, I believe, rarely seen farther east than Maryland. It seems to give a preference to maritime districts, or the neighbourhood of water. Although shy in the woods, it is half domesticated in and about our cities and villages, where it finds food without the necessity of using much exertion.

Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans, Natchez, and other cities, are amply provided with these birds, which may be seen flying or walking about the streets the whole day in groups. They also regularly attend the markets and shambles, to pick up the pieces of flesh thrown away by the butchers, and, when an opportunity occurs, leap from one bench to another, for the purpose of helping themselves. Hundreds of them are usually found, at all hours of the day, about the slaughterhouses, which are their favourite resort. They alight on the roofs and chimney-tops, wherever these are not guarded by spikes or pieces of glass, which, however, they frequently are, for the purpose of preventing the contamination by their ordure of the rain water, which the inhabitants of the southern States collect in tanks, or cisterns, for domestic use.

They follow the carts loaded with offal or dead animals to the places in the suburbs where these are deposited, and wait the skinning of a cow or horse, when in a few hours they devour its flesh, in the company of the dogs,, which are also accustomed to frequent such places. On these occasions they fight with each other, leap about and tug in all the hurry and confusion imaginable, uttering a harsh sort of hiss or grunt, which may be heard at a distance of several hundred yards. Should eagles make their appearance at such a juncture, the Carrion Crows retire, and patiently wait until their betters are satisfied, but they pay little regard to the dogs.

When satiated, they rise together, should the weather be fair, mount high in the air, and perform various evolutions, flying in large circles, alternately plunging and rising, until they at length move off in a straight direction, or alight on the dead branches of trees, where they spread out their wings and tail to the sun or the breeze. In cold and wet weather they assemble round the chimney-tops, to receive the warmth imparted by the smoke. I never heard of their disgorging their food on such occasions, that being never done unless when they are feeding their young, or when suddenly alarmed or caught. In that case, they throw up the contents of their stomach with wonderful quickness and power.

The Carrion Crows of Charleston resort at night to a swampy wood across the Ashley river, about two miles from the city. I visited this roosting place in company with my friend John Bachman, approaching it by a close thicket of undergrowth, tangled with vines and briars. When nearly under the trees on which the birds were roosted, we found the ground destitute of vegetation, and covered with ordure and feathers, mixed with the broken branches of the trees. The stench was horrible. The trees were completely covered with birds, from the trunk to the very tips of the branches.

They were quite unconcerned; but, having determined to send them the contents of our guns, and firing at the same instant, we saw most of them fly off, hissing, grunting, disgorging, and looking down on their dead companions as if desirous of devouring them. We kept up a brisk fusilade for several minutes, when they all flew off to a great distance high in the air; but as we retired, we observed them gradually descending and settling on the same trees. The piece of ground was about two acres in extent, and the number of Vultures we estimated at several thousands. During very wet weather, they not unfrequently remain the whole day on the roost; but when it is fine, they reach the city every morning by the first glimpse of day.

The Carrion Crow and Turkey-Buzzard possess great power of recollection, so as to recognise at a great distance a person who has shot at them, and even the horse on which he rides. On several occasions I have observed that they would fly off at my approach, after I had trapped several, when they took no notice of other individuals; and they avoided my horse in the pastures, after I had made use of him to approach and shoot them.

.jpg)